At a playwriting workshop recently, a fellow writer said, “Sometimes you create, sometimes you produce.” I knew what she meant. In writing fiction, be it in narrative form or for the stage, characters, scenarios, and even entire worlds emerge in passionate moments — creative sessions where imagination holds court and ideas come easily. It’s crucial not to inhibit this flow. A story’s form should be organic— the moves it makes, the shape it takes. Initial visions of setting, theme, voice, and plot emerge as the writer intuits what the story needs without the anchor of minutia holding things back. Art is made.

Afterward though, passion must meet practicality. Imagination is reconciled with feasibility. Rules are applied, and the piece is crafted into usable form. This later, deliberate work ensures that every detail in a story matters, and that the prose is made lustrous and precise.

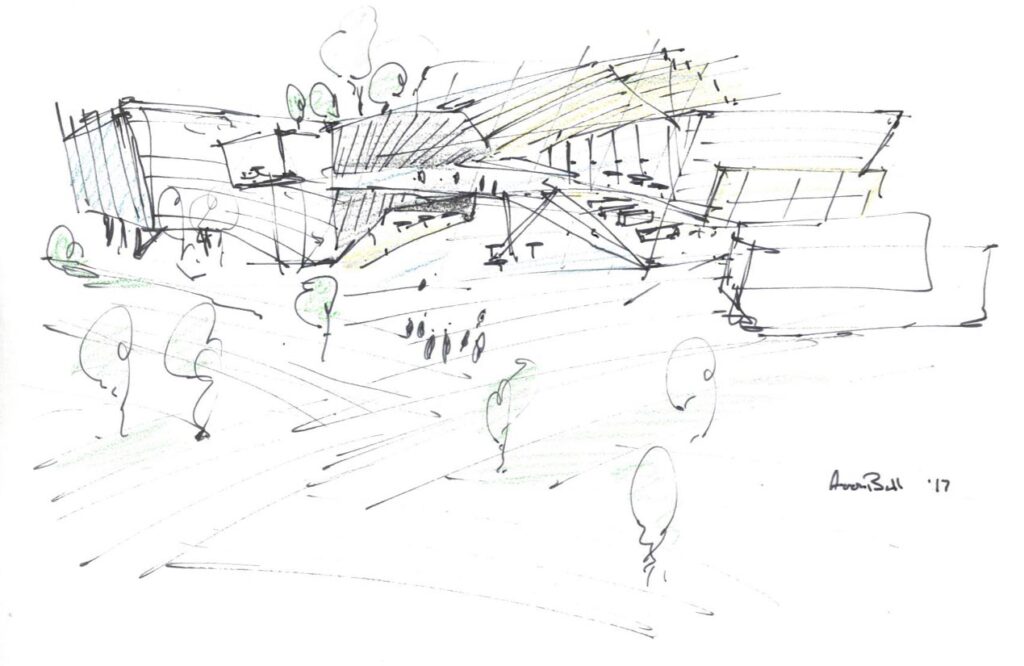

I find the creative process to be similar in the practice of architecture. During design charettes, we hear things like, “What could this space be if there were no limits?” Or, “How could an element of light transform the experience?” Or, “Let’s try to increase the sense of verticality.” There is creative freedom in envisioning a space. Overall form, quality, and atmosphere—the big story ideas—are contemplated, while future details wait. Methods to achieve the vision will be explored, rules and materials considered, but that will come later — the immediate moment is best served when left free.

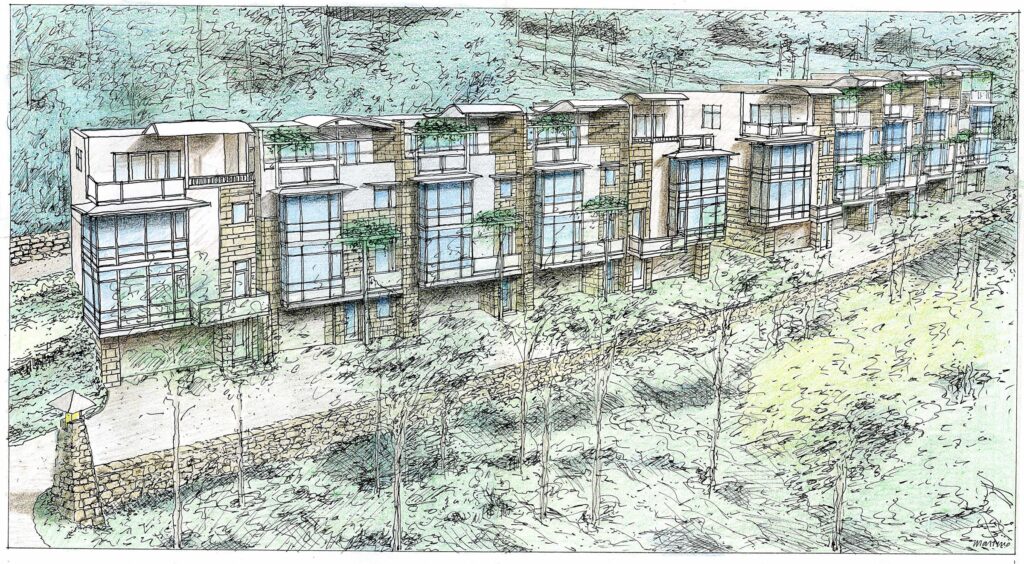

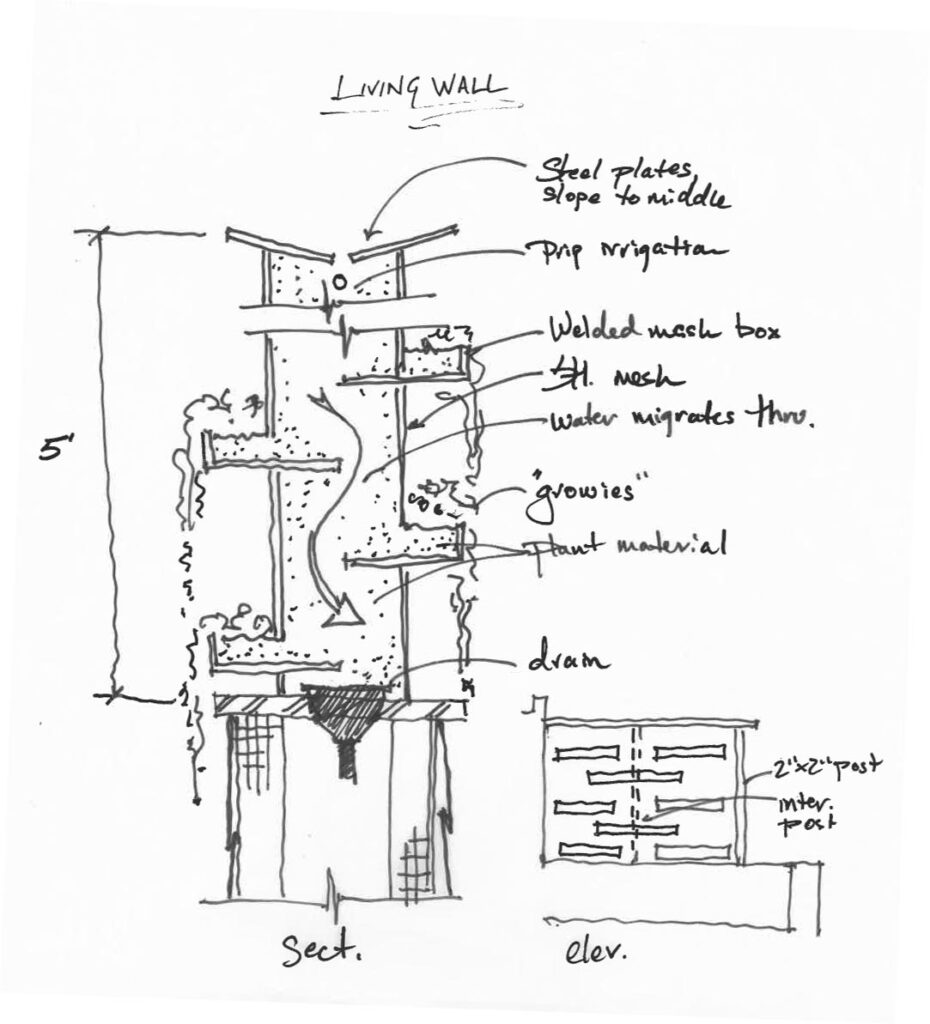

As the process is furthered, ideas are refined:

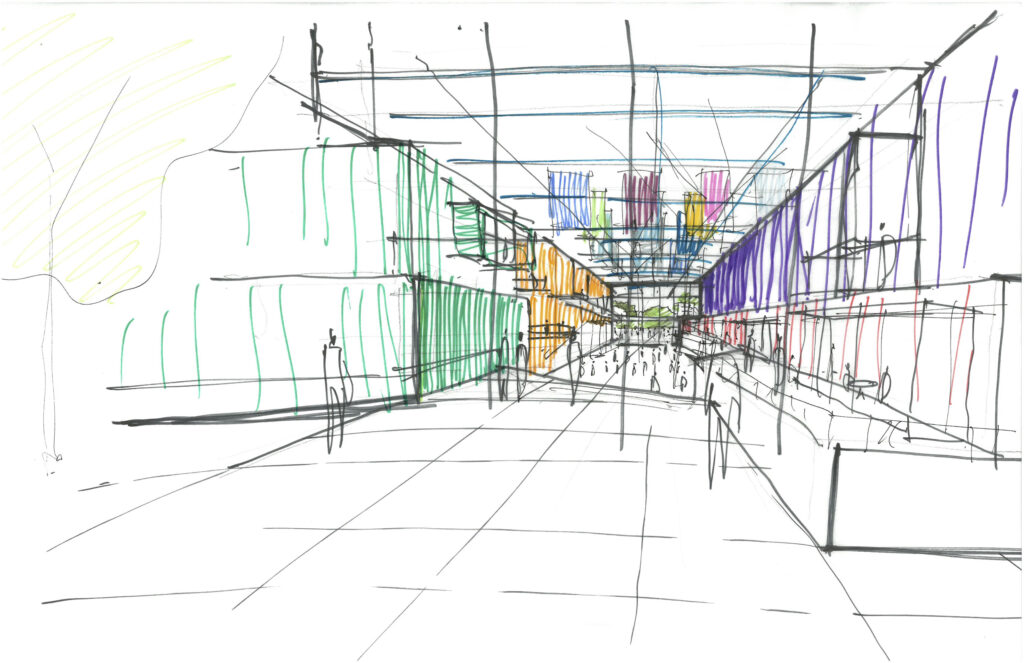

And furthered still:

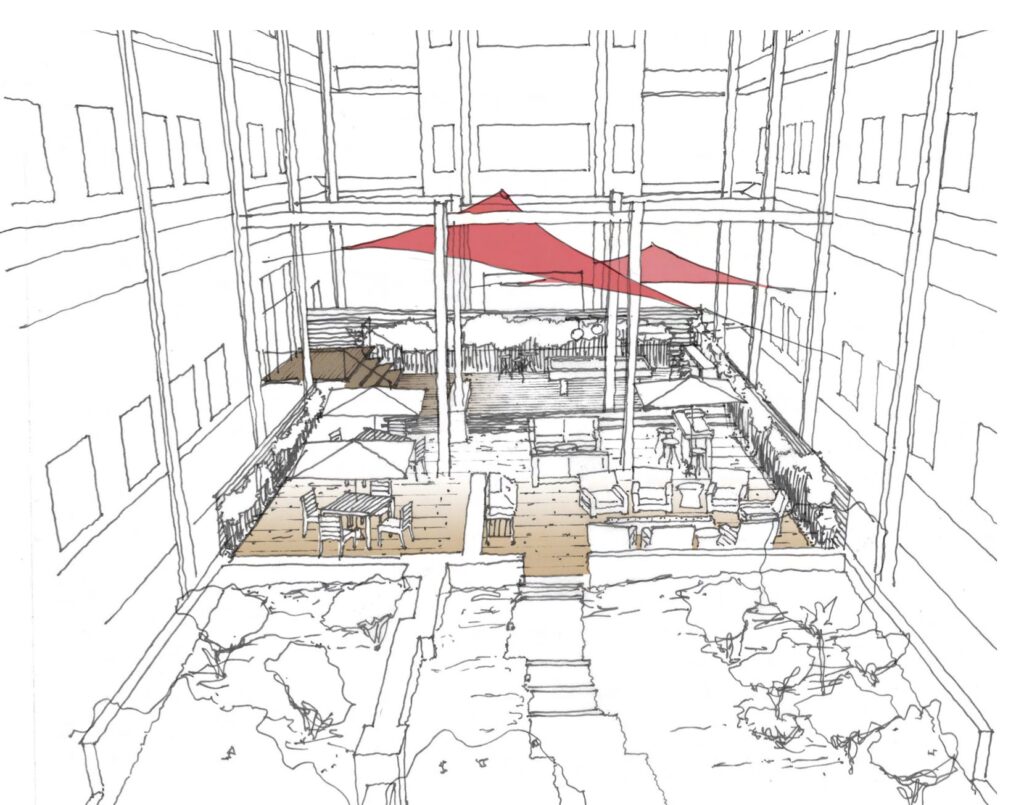

Once an initial vision has been solidified, so begins the work of its realization. Structure is planned. Elements that will comprise the whole are reconsidered and refined so that the result will make sense — beautiful, cohesive, sense. Careful attention is given, with every element included for a reason.

These differing facets — initial vision and technical requirements — need not conflict. They aren’t oppositional, but are complimentary parts of the creative process. And neither part is ever fully isolated. Initial creative flow keeps in mind fundamental rules, but concerns about detailing don’t stifle the early work. Spillover occurs. Contradictions are navigated. The design is refined, moving the idea from the gross to the fine.

There’s a need for flexibility in both stages of the process. Some early ideas ultimately prove to be unworkable, and regardless of our being enamored of them, simply have to go. In William Faulkner’s famous words, we sometimes must “kill our darlings.” Similarly, design refinement — from the first reshaping, to the smallest details drawn late in the process — should not stray too far from the initial inspiration. The vision seen in those early, passionate, creative moments must guide the design, must not get lost along the way.

It’s in that sweet spot between inspired, imaginative play and deliberate, discerning craftwork that truly successful design occurs. Where balance is achieved and vision is realized…